"The True History of the Conquest of New Spain" or Is It?

It‘s often said that ‘victors write the history books.’

I find that to be untrue— all of my history textbooks were written by Houghton Mifflin.

Corny jokes aside, we usually take this phrase to mean that those who come out on top in conflicts have the power to shape the narrative going forward—disparaging their opponents' names while making themselves look better in the process.

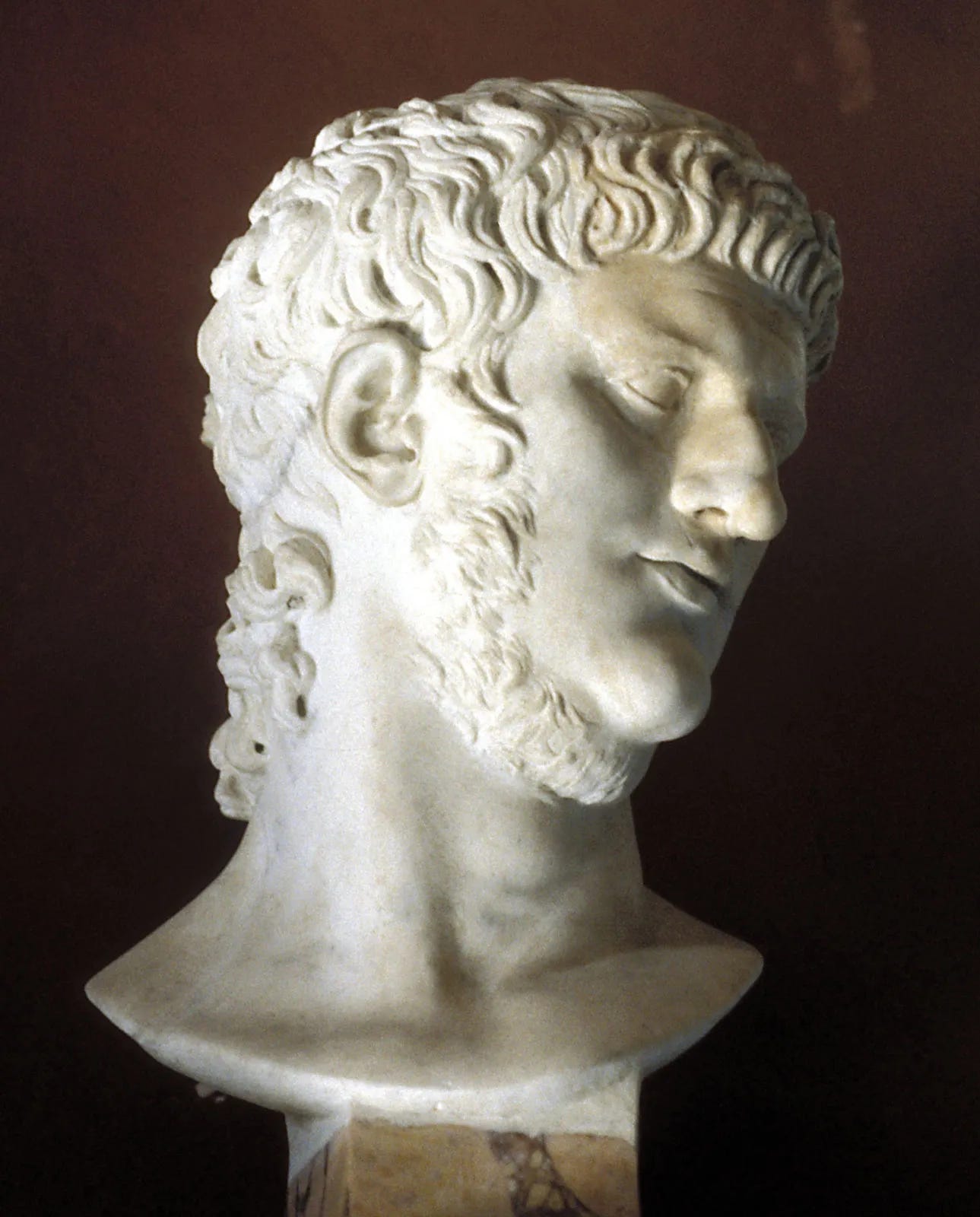

Take the case of Emperor Nero—"The Beast of Rome." Nero’s legacy is filled with tales of unspeakable cruelty: murdering his mother, beating his pregnant wife to death, setting Rome on fire and blaming the Christians, even castrating a young boy and forcing him to pose as his deceased wife. To this day, Nero is seen as one of history’s ultimate villains.

The truth, however, is a bit more nuanced: almost all of what we know about Nero was written by his political opponents (Tacitus, Suetonius, and Cassius Dio), who all had it in their best interest to denigrate Nero’s name—in fact, this was a common political strategy in ancient Rome called Vituperato.

Not only that, but their accounts are suspiciously similar to Roman mythology and literature, again raising questions about their accuracy. All this time, Nero could have been completely innocent—or at least not the maniacal monster he was made out to be.

These Roman elites did such a good job dragging Nero’s name through the mud, that even centuries later, Nero’s image as the embodiment of evil remains largely unquestioned, with some even considering him the antichrist. Dick move, if you ask me.

This sort of dynamic where winners write the story has repeated itself often throughout history—one such repetition is the European conquest and colonization of the Americas.

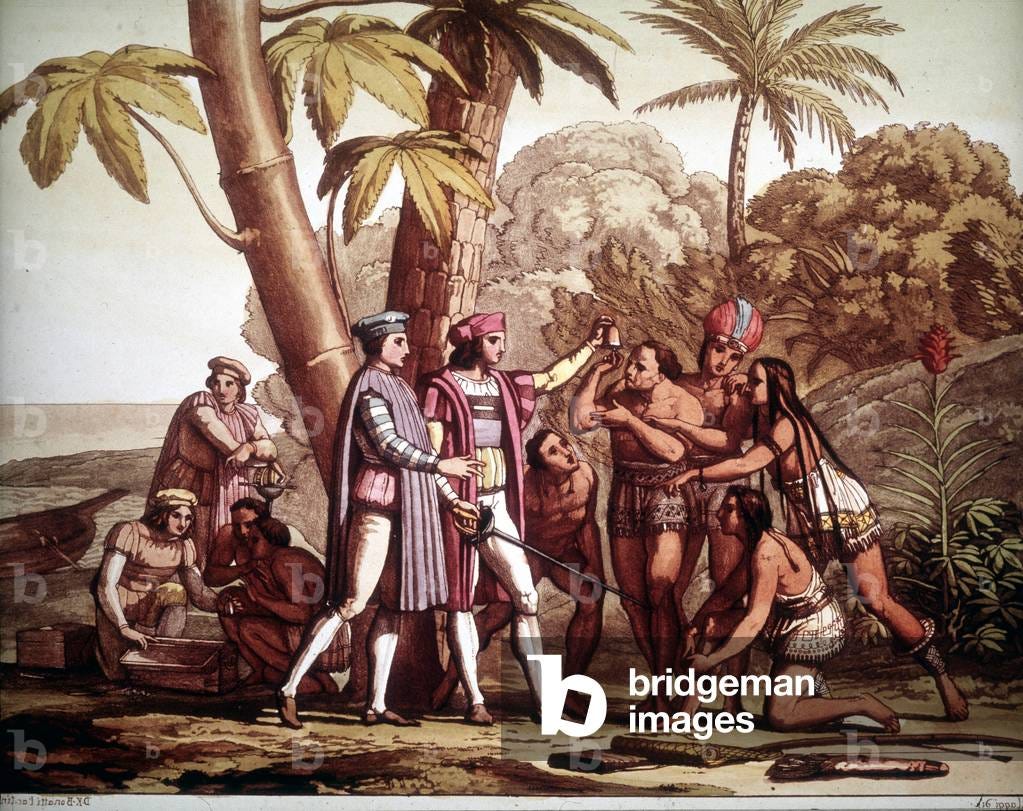

Consider how, in his journals, Christopher Columbus, described the local Taino people of Hispaniola as “on the whole to me, to be a very poor people,” and later noted that their docile nature would make them ideal slaves and easy to convert. His remarks were based on nothing more than the fact that the Taino offered him gifts upon his arrival.

That’s why I was so surprised when I came across La Historia Verdadera de la Conquista de la Nueva España (The True History of the Conquest of New Spain), a memoir written by Bernal Diaz de Castillo, recounting Hernan Cortez’s expedition into the Americas and his conquest of the Aztec empire.

Why would Díaz write this way? Wouldn’t it have been more effective to dismiss the Aztecs as barbarians, like Columbus did with the Taino, to justify their conquest?

Diaz’s writing may be evidence, that winners don’t always need to be assholes.

In one chapter, Díaz describes the grand entrance of Cortez’s party into Tenochtitlan, marveling at the city’s breathtaking infrastructure and beauty, stating: “With such wonderful sights to gaze upon, we did not know what to say”.

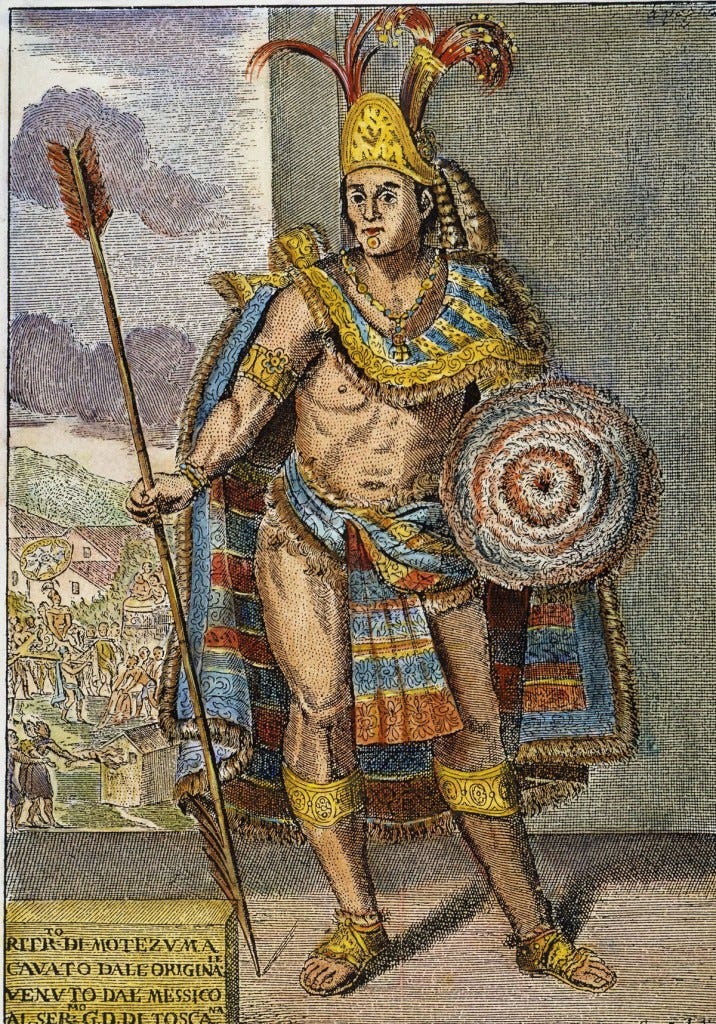

He goes on to describe Emperor Moctezuma as “magnificently clad” and surrounded by immense wealth, even noting that the emperor had “secret chambers containing gold bars and jewels”.

In another chapter, Diaz details a banquet held by Moctezuma, where “three hundred dishes of various kinds were served up for [Moctezuma] alone.” Even the emperor’s most trusted counselors would eat standing, forbidden to look at him—that is if they were even offered food.

His depiction bears strange similarities to the lavish banquets of European royalty, such as those of King Louis XIV at the Palace of Versailles.

This admiration is even more puzzling when you consider that Díaz wrote this memoir on his deathbed in 1568, almost 50 years after the fall of Tenochtitlan. By then, the Aztecs had long been defeated, and Spain had firmly established its dominance over the Americas. There seemed to be no diplomatic benefit in portraying the Aztecs in such a positive light.

In line with the Roman elites and their concept of Vituperato, as well as my boy Chrissy Columbus, it seems like it would’ve behooved Diaz, and Spain as a whole, to paint the Aztec people as barbaric savages whose conquest and subjugation was justified in the name of God and Christ.

Doing so, would have been easy too. The Aztecs had some pretty brutal customs—often conducting ruthless, unprovoked attacks on their tributary nations, for the sole purpose of collecting prisoners to sacrifice—and occasionally eat. In years of drought, it’s documented that there would be thousands of these human sacrifices…

Despite all of this, Diaz portrays the Aztecs as a powerful, vigorous, and complex people, without clear benefit. Why?

At first glance, it seems like Diaz was valuing historical accuracy and leaving the Aztecs a positive legacy. Maybe he wasn’t as self-serving as Tacitus or Columbus. Unfortunately, that’s not quite the case.

According to Dr. Nancy Finch of the American Historical Association, Diaz’s aim in writing La Historia Verdadera wasn’t to be a cool, genuine guy, but rather to “remind the King of Spain of the heroism of the Spanish conquistadors who accompanied Cortéz”.

By painting the Aztec culture as wealthy and grand, Diaz argues that the accomplishments of him and his peers were that much more impressive. In other words, they didn’t just take over some primitive tribe with sharp sticks, but a grand and powerful kingdom—despite being massively outnumbered, with only 400 Spanish soldiers facing thousands of Aztecs. At one point in the chapter, Diaz asks the reader, “What men in all the world have shown such daring?”.

This idea comes through in the text too: Diaz describes how, during the banquet, after being served human flesh (yum), Cortez “reproached [Moctezuma] for the human sacrifices and for the eating of human flesh.” According to Diaz, Moctezuma ordered that no more human dishes be served after this.

It’s hard to imagine that Cortéz could have scolded Moctezuma in front of his own court—where his advisors wouldn’t even dare look him in the eye—and walked away unscathed.

While this scene might seem counterintuitive to portraying the Aztecs as a great kingdom, it is meant to show that even in the face of a mighty empire, the Spaniards maintained their sense of “civilization.” Not only were they brave, but also morally superior—and thus justified to conquer and convert.

Although Diaz’s admiration for the Aztecs stands in stark contrast to the documents of the time, it still shares the same purpose: to make the writer look good. His memoir is ultimately meant to amplify the heroism of the conquistadors, not to show admiration for the Aztecs—that was just a byproduct.

The point I’m making is that it’s not as simple as to say the winners make themselves look good and their enemies look bad. History is more subtle—It’s shaped by the time and people who write it.

By the 1560s, Spain’s global dominance was already beginning to decline, and Diaz, as a former conquistador likely held in high regard, sought to rekindle the conquistador spirit in King Philip II, reminding him of Spain’s former glory—and the future possibility of gold.

In the end, it seems like Bernal Diaz was still writing a winner’s history. Due to this, La Historia Verdadera leaves us with a major misconception about the Spanish conquest:

That Spain’s victory was inevitable due to its intellectual and technological superiority over the indigenous peoples of the Americas, despite their prowess.

The truth is that Spanish victory was far from certain. The Spaniards supposed technological advantages—15 shitty guns, 10 cannons, and 16 horses—were basically a non-factor in the face of an army numbering in the hundreds of thousands.

What gave the Spaniards the W, was luck in the form of Moctezuma’s terrible decision-making, a devastating smallpox epidemic that killed around 90% of the natives, and the fact that the surrounding nations despised the Aztecs.

This luck allowed Cortez to secure an army of around 50,000 Tlaxcalans (who hated the Aztecs) and lay siege on a dying, sickly population after Moctezuma had died in captivity. And even that was a big struggle.

Looking at historical inconsistencies like these is fascinating to me—they’re like puzzles. They constantly remind me things aren’t always black and white—especially when it comes to history.

Diaz may not have been as big of an asshole as Columbus, but he is proof that context always matters. Even when a situation seems ‘average’, it is always worth taking a deeper, and more critical look to uncover the truth. In the words of Alex Russo from Wizards of Waverly Place, “Everything is Not What It Seems”.

Works Cited

Díaz del Castillo, B. (2019). Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España. Real Academia Española. https://www.rae.es/sites/default/files/Aparato_de_variantes_Historia_verdadera_de_la_conquista_de_la_Nueva_Espana.pdf

Finch, N. (2021, September 27). Bernal Diaz Del Castillo: AHA. American Historical Association. https://www.historians.org/teaching-and-learning/teaching-resources-for-historians/teaching-and-learning-in-the-digital-age/the-history-of-the-americas/the-conquest-of-mexico/narrative-overviews/some-interpretive-ideas/bernal-diaz-del-castillo

Horses. (2023, September 13). Nero: The monster of Rome [Video]. YouTube.

Joe, this was a great read. Enjoyed it greatly and such a unique story

Bravo!